Functions

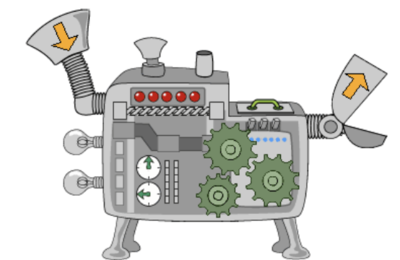

This lesson introduces how to define your own functions. A function is a subprogram that, given several inputs, calculates a result. We can imagine a function as a machine that transforms inputs into outputs. Unlike programs, functions usually do not interact directly with the user by reading data from the input channel and/or writing the corresponding results to the output channel.

Functions are a fundamental mechanism for decomposing a program into different subprograms and, therefore, for solving a complex problem using solutions to simpler problems. Functions allow writing more readable and structured programs, and make them easier to debug and improve. And, although we will not see it in this basic course, functions also provide a way to share code between different projects.

Function for the maximum of two integers

Let's consider that we want to write our own function to calculate the maximum of two integers. Yes... this function already exists as the predefined max function, but it will be useful to see how it is made.

First, we start with the header of the function, also called declaration or interface:

def maxim2(a, b):

...This header informs the following characteristics:

- The name of the function is

maxim2. - This function has two parameters, the first is called

aand is an integer, the second is calledband is also an integer. - The result of the function is an integer.

It is good practice to write the purpose of each function in a note called specification. In Python, this is done with a docstring, which is a text placed right after the header. Since these specifications are often long and span more than one line, they are written between three double quotes:

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

...Next, the body of the function is given:

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

if a > b:

m = a

else:

m = b

return mNotice how the body of this function is very similar to a program that calculates the maximum of two integers and stores the result in m, but instead of printing the value of m with a print, the function returns this value with a return.

The return indicates that the function has finished its job and delivers as a result the expression on its right. In this case, the function maxim2 simply returns the value of m.

In fact, we can simplify the body a bit by avoiding the variable m with two return statements, one for each branch of the conditional:

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

if a > b:

return a

else:

return bWe can even remove the else because, upon encountering a return, the function finishes its job and immediately delivers the result, without continuing to execute the rest of the code that follows:

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

if a > b:

return a

return bTo use a function from a part of the program, you must invoke it in the same way we have done with predefined functions. This complete program can be used to test the maxim2 function:

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

if a > b:

return a

else:

return b

print(maxim2(34, 67))Function for the maximum of three integers

Now we want to make a function that, given three integers, say a, b, and c, returns the largest. Its header and specification could be

def maxim3(a, b, c):

"""Calculates the maximum of three integers."""To implement the body of this function, there are basically two solutions:

The first consists of doing a case analysis using conditionals, and there are many possible variations. Here is one that is quite clear:

pythondef maxim3(a, b, c): """Calculates the maximum of three integers.""" if a >= b and a >= c: return a elif b >= a and b >= c: return b else: return cThe second, smarter, consists of taking advantage that we already have a written function

maxim2and, therefore, we can use it! This would be one way to do it:pythondef maxim3(a, b, c): """Calculates the maximum of three integers.""" return maxim2(maxim2(a, b), c)As this code shows, a function can invoke another function. Not only that, it can invoke it two or more times, and with different parameters. In other words, subprograms can freely use other subprograms.

Although the first solution is not excessively complicated, the second is even simpler and, therefore, preferable. Designing functions that solve increasingly complex tasks by leveraging simpler functions is an excellent design practice.

For reference, this is the complete program that reads three integers and writes the maximum using the function maxim3(), which, in turn, uses the function maxim2():

from yogi import read

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

if a > b:

return a

else:

return b

def maxim3(a, b, c):

"""Calculates the maximum of three integers."""

return maxim2(maxim2(a, b), c)

# main program

x = read(int)

y = read(int)

z = read(int)

print(maxim3(x, y, z))In Python, the order of function definitions is not relevant, but the main program must go at the end.

Formal parameters and actual parameters

You have already seen that when writing the header of a function, its parameters are listed, giving their name and type. These parameters are called formal parameters and serve to name the input data to the function. I also like to think that they "give shape" to the function. For example, in the following function,

def maxim2(a, b): ...a and b are its formal parameters. The body of the function will use a and b to refer to the values it must work on when invoked.

Precisely, when a function is invoked, the necessary values that will be received by the formal parameters must be passed. These parameters used when invoking a function are called actual parameters (or arguments). It is useful to think that the actual parameters are the values on which the function "really" has to work.

For example, in the expression (maxim2(10, x) + maxim2(x, x + y)) / 2 there are two invocations of maxim2. In the first, the actual parameters are 10 and x; in the second, the actual parameters are x and x + y. In fact, the actual parameters are the result of these expressions, since actual parameters are values.

When invoking a function, the value of the actual parameters is transmitted to the formal parameters:

In the first invocation, the formal parameter

awill receive the value10and the formal parameterbwill receive the value that the variablexhas at that moment.In the second invocation, the formal parameter

awill receive the value ofxand the formal parameterbwill receive the sum of the values ofxandy.

Note that formal parameters are expressions that produce a value (10 or x or x + y). On the other hand, formal parameters are variable names with their type.

The variables of the formal parameters receive the values of the corresponding actual parameters when the function starts, just as if they were assigned. In fact, Python performs an assignment for each parameter.

Formal parameters and variables are local to functions

Consider the following program, which is a variation of some of the previous ones:

from yogi import read

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

if a > b:

m = a

else:

m = b

return m

def maxim3(a, b, c):

"""Calculates the maximum of three integers."""

m = maxim2(maxim2(a, b), c)

return m

# main program

a = read(int)

b = read(int)

c = read(int)

print(maxim3(a, b, c))In this program, there are two variables named m, one inside the function maxim2() and another inside the function maxim3(). Although these two variables have the same name, they are two distinct variables. That is, each variable belongs to the function within which it is defined. We say that these variables are local variables.

The locality of variables is very useful because, when writing a function, you do not want to have to check the names of variables that may exist in other functions (which perhaps were not even written by the same programmer!).

Formal parameters are also local: The parameters a and b of maxim2() have nothing to do with the parameters a and b of maxim3(). In fact, in the first invocation of maxim2() inside maxim3(), the value of b of maxim3() is copied to the parameter a of maxim2(), and the value of c of maxim3() is copied to the parameter b of maxim2(). And, in the second invocation of maxim2() inside maxim3(), the value of a of maxim3() is copied to the parameter a of maxim2() (it is a pure coincidence that they have the same name) and the value of m of maxim3() is copied to the parameter b of maxim2().

Similarly, the fact that the three variables of the main program are named a, b, and c is only a coincidence with the fact that the three parameters of maxim3() are also named a, b, and c. However, these three variables, since they do not belong to any function, are called global variables and we will talk about them later.

In fact, there is not a single variable m for the function maxim2(), but there will be a different one each time the function is invoked. The execution system takes care of maintaining all these variables while they are needed, and recycling their memory when they become unnecessary.

If this section is a bit hard to understand, keep going and you will come back to it later. After all, what you need to know is that everything is designed so that the names of variables and parameters of functions do not interfere with each other.

Common errors

In this section, we will comment on two common errors that are often made when starting to use functions.

Reading data with a

readinstead of receiving it as parameters, or writing the result withprintinstead of returning it.For example, this program would violate these precepts:

pythondef absolute_value(x): """Returns the absolute value of a real number.""" x = read(float) # 😬 the value of x should not be read, it is a parameter! if x >= 0: y = x else: y = -x print(y) # 😬 the value of y should not be printed, it should be returned!The correct version would be

pythondef absolute_value(x): """Returns the absolute value of a real number.""" if x >= 0: y = x else: y = -x return yOr, more briefly:

pythondef absolute_value(x): """Returns the absolute value of a real number.""" if x >= 0: return x else: return -xNote: Later, when we know more, we will break this rule and make functions that do read or write through input/output. For now, however, doing this would be a sign of having made a mistake.

Giving types to actual parameters.

Remember that there are two types of parameters: formal parameters that help define the body of a function and actual parameters that are the values on which you want to invoke a function. It is advisable not to mix the two and realize that types are only given to formal parameters.

For example, if we have the function

pythondef maxim2(a, b):we should not invoke it with inventions like this:

pythonm = maxim2(x: int, 4: int)Types are placed in function declarations, not in invocations.

Functions without type annotations

One last observation: In Python it is not mandatory to annotate the types of functions and their parameters. One could, for example, define the function maxim2 like this:

def maxim2(a, b):

"""Calculates the maximum of two integers."""

if a > b:

return a

else:

return bAlthough this practice is legal, not annotating types implies having to document the code more extensively and makes it impossible to perform static type checks with tools like mypy or Pylance. For this reason, in this course, we will always annotate the types of all functions.

Jordi Petit

Lliçons.jutge.org

© Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2026